New Free Mini-Course for Subscribers

Great news! I have updated the free mini-course “Paint the Emotion” and it’s now called “Color the Emotion.” I have added a new project with colored pencils and more talk about how to approach art-making. The mini-course is about 40-minutes long and it’s available for all the subscribers of my weekly emails.

Here I am talking about the free mini-course in a video:

P.S. If you are already subscribed, no worries! I will send you an email today with the link to the mini-course!

Design Principles Translated to Intuitive Painting

This week, I talk about design principles for intuitive painters. This is for you who paint because it’s a spiritual act!

While making this acrylic painting, I thought about how intuitive painters often feel a disconnection with general art advice like “make sure you have a focal point.” Even if I teach online classes, I often find advice that solely focuses on the technical part misleading because it talks so little about artistic expression and the experience of making art. Design principles can be like a bible for technically oriented people and a blank book for those who want to approach the subject more emotionally. But it doesn’t have to be like that!

Design Principles and Intuitive Painting

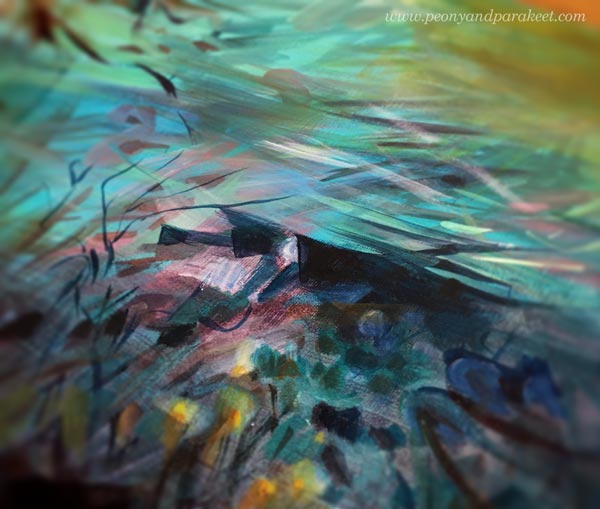

Intuitive painting differs from following a predefined idea, a reference photo, or a sketch. Let’s take the focal point as an example. Intentionally, you should start what matters the most and make it noticeable. This way, you have a clear focal point, and your painting delivers a clear message. But when you paint intuitively, there’s no message when you begin. The painting process is about connecting with your spirit and being open to what wants to come out. Here’s what my painting looked like after the first layers. Yes, there’s some resemblance with the finished piece, but not so much that the advice would make sense.

The focal point (the small pale yellow rectangle in the dark area) and its supporting element, the row of white dew drops, were added much later. Here are the dewdrops and the many layers more closely.

On the other hand, I don’t agree with those who say that lighting candles and taking a spiritual mindset should be enough. There are also those who believe in natural talent – that you either can or can’t paint – which I most strongly oppose.

For me, intuition is about bringing knowledge and creativity work together and listening to what they have to say. When I want to move forward, sometimes it’s about growing my knowledge, sometimes increasing my creativity, but often it’s also getting better at listening – quietly observing what the painting wants to become.

When I notice a shape that looks like it’s whispering to me, I want to strengthen it. And sometimes, these shapes later disappear under new ones, but they still showed me the way.

Let’s go through 7 design principles and translate them from intentional to intuitive painting.

#1 Emphasis

In intuitive painting, aiming for emphasis is often about finding a suitable title and adjusting the painting to express the title. For me, painting is quite far before the first ideas about the title come up. However, the first ideas are usually the most conventional ones, so I keep painting and diving deeper.

I thought this piece was finished, when it looked like this. The title that I had in mind was “Windy Tales” or “Wind Blows in a Fairytale.” But it was still too generic, so I kept asking: What fairytale?

After the painting session, knitting late at night, I got the answer: Snowwhite! So next morning, I added some more white and other colors of Disney’s Snowwhite.

I feel that these small adjustments released the spirit of the painting.

Intuitive doesn’t have to mean fast. We can take breaks and let our intuition and connection grow between the sessions.

#2 Balance and Alignment

The emphasis needs extra effort, but balancing is what we do naturally and so much that it suffocates expression. Be aware that “intuitive” often become “balanced” and nothing else.

The easiest way to balance a painting is to make it symmetrical. So taking an asymmetrical approach – even just for a couple of layers – makes you more expressive than any meditation! Imagine a horizontal and a vertical line in the center of your work and force yourself away from constant balancing strokes.

So for intuitive painters, getting off-balance is more important than creating a balance right from the beginning. In the end, you can balance the image with a few strokes if needed.

#3 Contrast

Intuitive painters have a strong connection to colors. I often begin with a specific color combination in mind, and colors feed my ideas. Yes, I like pinks, turquoises, bright yellows, bright greens … but I also have to remind myself that like a spring flower, a spirit of the painting rises slowly from mud.

This design principle is not so much having different colors, but having differences in lightness and darkness. For intuitive painters, it means that we have to process colors that we lay on the painting. So not just squeeze tubes, but to create our own color mixes so that the spirit is not only on the paper or canvas but also on our palette.

When we slowly create the color mixes, we have time to connect with the tone, adjust its darkness, seek for the genuine response that has a longer-term effect than what has been industrially produced.

#4 Repetition

The best way to think about repetition is to express echo. Instead of constantly balancing your painting by looking at the big picture, focus on one shape that you have just painted and imagine its spirit. How would the shape echo itself?

The echo is never identical to the original spirit. The echo is weaker, and there’s never just one sound, but a few.

#5 Proportion

In intuitive painting, we paint energy. Energy gathers to form cells, then clusters that get bigger and bigger. It’s easiest to see these clusters by looking at the painting from a distance or by taking a photo and reducing it.

If your painting is full of clusters, all the energy is static, and you need more openness in shapes and lines. If all the clusters are similar in size, then the overall energy is impermanent and less powerful.

#6 Movement

Intuitive painting connects us with the tradition of storytelling. We don’t just deliver a spirit but a story about its power. In visuals, we can build paths from one element to another so that the eye can effortlessly move around the painting like it’s listening to an impactful story.

Rather than painting separate elements, connect them with lines or layering one slightly over another. Make sure that all your elements are not round and stop the eye, but pointed that move the eye forward and build flow and movement. So, when you feel the connection with the painting, create connections visually too.

#7 White Space

Intuitive painting is less about arranging space and more about filling space, but white space is still relevant if you think about it as breathing. A painting doesn’t only need a spirit – it needs to breathe. If you paint boldly, everything bland will help with breathing. Adding muted yellows around a bright yellow spot makes the yellow spot breathe.

Design Principles Apply To All Art

So, you see, intentional and intuitive painting are not so different after all. The process and the values are a bit different. Still, it’s like humans – we come from different countries and cultures, speak different languages, but with some translation, we can feel togetherness across the borders.

If you like this article, you will love my class Floral Freedom! There I translate Paul Klee’s technical and Wassily Kandinsky’s spiritual teachings so that you can paint abstract florals freely. >> Buy Here!

Three Design Styles, a Gelli Plate, and a Brush

One of my goals for this year is to learn surface pattern design. I want to move back and forth between art and design, and add more design to this blog as well. This week, I picked three of my favorite designers and played with Gelli Plate to imitate their style. These don’t replicate any of their work, just their style.

Three Designers from Three Centuries

My three favorite designers are Tricia Guild, William Morris, and Wassily Kandinsky.

Tricia Guild a designer from the UK, and she has a company Designer’s Guild, and I have been her fan since the 1990s when I discovered her book Design and Detail. It’s been my interior design guide for 30 years, and all my homes have got ideas from that book.

William Morris is also English, but he lived earlier, in the 19th century. Two rooms of our home have curtains designed by his company, and I regularly admire their clever repeats and ornamental shapes.

Wassily Kandinsky was more of an artist than a designer, but he taught designers in a famous Bauhaus art school in the early 20th century. For me, he is the father of modern design. I see his paintings in the works of most midcentury modern designers. Lately, he has felt even closer, when I have been built a class Floral Freedom that is based on his and Paul Klee’s teachings.

Who are your favorite designers?

Three Designers – Three Color Palettes

I have always liked making hand-decorated papers. Actually, my most popular blog post is this ancient one: How to Make Your Own Patterned Paper from 2010. So let’s get back to basics and make some!

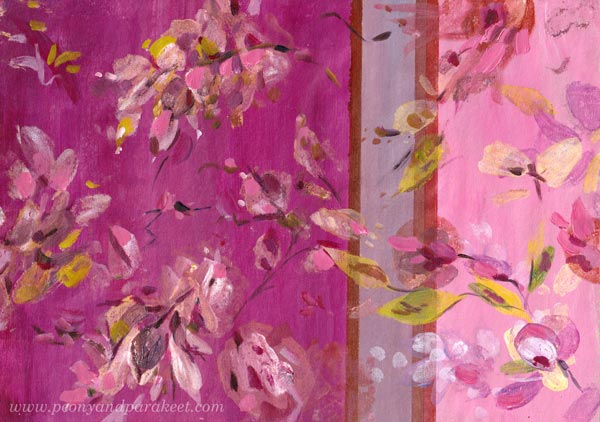

First, I painted the backgrounds with acrylic paints and a flat brush. This set a color palette for each paper.

Muted pastels and rich darker tones remind me of Tricia Guild. She often uses stripes or checks too. William Morris has greyish colors and many of his designs have dark backgrounds. Wassily Kandinsky often had a very light background in his paintings.

Three Design Styles – Three Kinds of Shapes

I continued each of the papers by mono-printing motifs with a Gelli Plate. For Tricia Guild’s style, I used a small plate and painted the motifs with a brush on a plate, then pressed the plate on the paper. Because Tricia’s style is often quite relaxed, there was less pressure for perfect outlines.

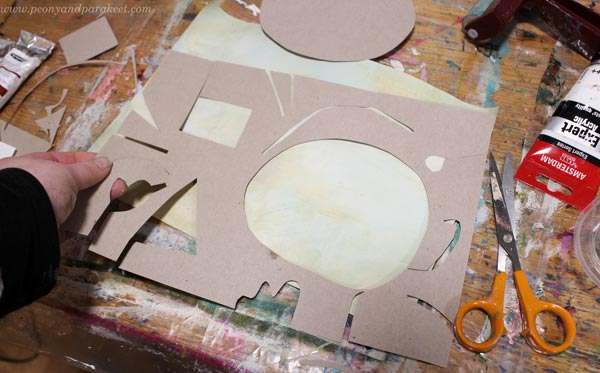

William Morris’s designs are very sharp and ornamental. I cut out ornaments freehand from paper and used both negative and positive shapes. I used both a big Gelli Plate and a small one.

Here’s how the paper looked after mono-printing.

Wassily Kandinsky’s shapes are mostly geometric, so I cut templates that had circles, lines, squares and triangles.

Here’s how the paper looked after mono-printing.

Three Design Styles – Three Levels of Detail

After mono-printing, I finished the papers by painting. I used a narrow brush and made small tweaks only.

I like Tricia Guild’s designs because there modern meets classic and historical. They feel luxurious, but still comfortable. They don’t require similar perfection from the space than William Morris’s designs. So I didn’t perfect every shape or line, just added a bit more realism to the floral motifs. Here’s the finished paper.

William Morris’s designs are full of outlined motifs, and I connect them with books. “For people who have a library,” I wrote in a notebook that I keep for studying. But I quite liked my mono-print, and didn’t want to stiffen everything. So I only outlined a part of the motifs, and added some small dots and thin lines inside the shapes.

Here’s the finished paper. I really like the big yellow motif! Maybe that could be a part of my future designs.

Wassily Kandinsky’s work didn’t lack details either. But if William Morris is for bookworms, then maybe Wassily is for systematic thinkers – for more scientific than humanistic introverts, and for those who love mathematics.

I used the monoprint as a foundation for the composition of shapes and followed Wassily’s advice and ideas from his book Point and Line to Plane, the book that I teach in the class Floral Freedom as well. Here’s the finished paper.

Three Wallpapers

I wanted to see how these papers could work as repeats. I didn’t have time to play with the repeats properly, but here are some quickly made images to demonstrate how the motifs would look in a smaller scale, for example, as a wallpaper.

It was a full day, but I had fun making these! Tell me, which three designers would you pick?

No Creative Blocks – Painting Grief and Loss

Even if I want these blog posts to be a celebration of art-making, I also want to paint and write from the heart. This week’s post is about sadness and its’ effects on creativity.

Here’s my latest acrylic painting called “If Grief Smoked.” Like many of the recent paintings, this also has a connection to a poem. The title is from Eeva-Liisa Manner’s poem “Jos suru savuaisi.” But this time, I didn’t follow the poem but used the title as a prompt only.

Missing Cosmo

I have been very melancholic this fall, and to be honest, building a new class Floral Freedom, has been my savior. It’s been a captivating escape from a life that feels emptier than before. My loyal companion Cosmo died in September, and it’s like a part of me has lost a purpose.

Cosmo was our family member for over 15 years, and there’s a lot I miss about him. Small things, often quite insignificant ones, like how he used to pick a sock when he wanted attention. My heart breaks when I remember how softly he did that, not leaving a single mark. In the end, he was a good dog and didn’t want to behave badly.

So yes, my grief has been smoking and burning. A wind of time has taken some away but also spread it further. When it started to feel that the grief would scorch my brushes, destroy the paints, and make the studio a smoky place, I knew it was time to paint. Not that it would take the grief away, but force me to deal with it.

Persuasion Can Replace Inspiration

Art is not always about inspiration. You know Picasso’s saying that the inspiration has to find you working. I find self-persuasion especially useful. “After this, you can paint whatever you want,” I said to myself.

If we don’t paint these paintings that need to come out, it can cause a creative block. I have had some major ones in the past, and I didn’t want that to happen now.

“Follow the color,” I said to myself like many times before. It’s a quote of my own that boosts my confidence when I am working.

Stepping Into The Painting

This scenery had been in my mind for weeks. It was like an overdue baby, pushing through the brush.

I just had to open my heart and welcome it.

Wassily Kandinsky talks about a glass between the artist and the painting, and how to remove it. It’s one of the hardest things when in grief, but also the most impactful one.

When we paint without the glass, the image becomes more personal. It doesn’t matter what other people think about it because you are living and breathing it. But oddly so, removing the glass also makes the image more general. My loss gets connected to everybody else’s losses. We are all behind the same glass, under the same blanket.

If grief smoked, we would all be covered in it. Even if it’s the saddest thing, it’s also beautiful to let go of someone or something you love. You can no longer help them, and it’s time to give them away.

Mental Queue – Images That Need to Get Painted

Art helps us with things that can’t be solved intellectually. I also think that artists have a mental queue. If we try to jump over the hard images, we don’t have the energy for the more cheerful ones that come next.

I hope this inspires you to pick the brush and paint the image that has been waiting for its turn.